Jodhpur, the Blue City, the Sun City, sits in the geographic center of Rajasthan. Jodhpur peaked in prosperity and wealth during the middle ages, serving as a hub for trade in spices, textiles, and opium. Being here, it isn’t hard to imagine caravans of weary merchants riding into the city’s bazaars on numerous parched dromedaries.

Jodhpur’s main point of orientation is its massive citadel, Meherangarh Fort. Claimed to be one of the largest forts in the world, it seems not to have been built but rather carved, from the top down, out of the mountain that serves as its foundation. In fact, I have yet to take a single picture of its entirety…it is one of those things whose enormity cannot be captured on film. A single snaking road leads up to the fort’s towering outer bastions. As it nears the gate the path tapers at sharp angles in an effort to deter the rampaging charges of attacking Jaipurian elephant regiments. Evidence of those epic battles can be found in the fort’s ramparts that are scarred and pockmarked with dozens of cannonball explosions.

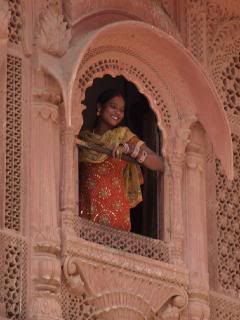

Inside are countless linked courtyards, surrounded by ornate pathways walled by exquisite marble latticework. Golden rooms spill into pearled hallways which lead to ruby-studded atriums. Quiet and uninhabited now, it is nevertheless easy to imagine the commotion of Rajput warriors and royal women who once existed here. Concealed in its beauty, the fort is not without its share of tragedy. On one of the interior walls are thirty-one small handprints, carved into the red stone; the last testament of Maharajah Rau Jodhah’s surviving wives before they were immolated on his funeral pyre in ritualistic “sati,” the ultimate act of devotion, or as I see it, the ultimate act of compulsion.

Sati handprints at Meherangarh Fort

-----------------------------

Under the western shadow of the fort lies Sardar Market, a sprawling bazaar centered around a beautiful pre-Mughal clock tower. Vendors sell everything from exotic fruits and vegetables to incense and hand-rolled bidis. One can buy a stereo for four dollars, or a kurda for half that. Teetering pyramids of clay water vessels sit in front of textile shops that trade in block printed fabrics and tie-dyed tapestries. Shirtless men feed long staffs of sugarcane into mechanical grinding contraptions. Wiped “clean” with oily rags, they sell grimy glasses of pure sugarcane juice, flavored as much by the sweat of their labor as the raw cane sugar.

If you venture from the market, you become delightfully, hopelessly lost in a labyrinth of medieval alleyways. Soon you are in Brahmapuri, where everything but the family dog is painted sky-blue to signify the presence of spiritually superior Brahman caste members. There doesn’t seem to be any method to the random layout of tentacle backstreets. Perhaps, though, I have seen too many six lane highways I my life to ever be able to understand this madness.

Brahmapuri seen from Meherangarh Fort

A few nights ago I was wandering the alleys of Brahmapuri, searching for a rickshaw after having eaten at an underground, lower-caste tandoori pit. Head down, trying in vain to avoid the stares of toothless, sari clad women, I rounded a corner and was suddenly face to face with one of the city’s innumerable 2,000-pound bovine. In other neighborhoods such an encounter would not present much of a problem, however, due to Brahmapuri’s four-foot wide passages this was an entirely different story. Hindus believe that cows are the reincarnations of passed loved ones. With this in mind and, invoking at once the blessings of Shiva, Hanuman, Prita, Sita, Kali, and Vishnu, I squeezed by, protecting with my hands my most valued organs. Not to let me off too easy the beast whipped around and stuck me in the flesh of my thigh with its blunted horn. “Screw you, buddy,” I thought aloud. “I should’ve known you were a bastard in a past life!”

-----------------------------

Leaving the area immediately surrounding Meherangarh Fort, the streets become wider. Cascades of raw sewage no longer flow in cut channels along soot covered plaster homes. People don’t stare as intently, or as accusingly for that matter. Occasionally, in these more suburban regions within the city, a dark haired, fire-eyed beauty can be spotted defiantly strutting in tight fitting blue jeans. Such sightings, however, are unfortunately few and far between.

I have found it difficult to walk very far without being stopped by someone on the street. Young, curious, semi-fluent young men seem to see me as an opportunity to improve their English conversational skills. All of them offer their cell phone numbers; many extend dinner invitations in heart-warming exhibitions of Indian hospitality. Rickshaw drivers, as well, pull to the left side of the road, creeping along to match my stride. “Where going,” they ask, or simply, “get in, boss.” Usually dismissing them with a flick of my wrist, most look bewildered that a rich foreigner would prefer to walk. It is interesting and, I suppose, one of the many manifestations of post-colonial stereotyping in India, that no matter my appearance (think bearded dude wearing ratty tie-dyed shirt) I am almost always perceived as immensely wealthy. Now, I’m not saying that this is always a bad thing; for instance, I’ve never had such good bar service in my life. As any twenty-two year old, bar frequenting, stingy-tipping guy knows, bartenders in America can be a little aloof, if not downright callous. Here, it is completely different. “Would you like more peanuts of papad sir?”

“What television you like to see?”

“Would you prefer me to put on your cricket game?”

I try to leave generous tips; fifty rupees at the end of the night, the equivalent of one US dollar, leave everyone smiling.

------------------------------

In a land of immense faith, simple actions like crossing a busy street are enough to make one question their purpose in life. In situations such as these, I have found that faith is a necessity. You cannot wait for a break in traffic – there are none. Jaywalking in India is not unlike climbing. You visualize your route, give yourself a little pep talk, and in fluid yet dynamic movements you make your move. Don’t look back until you’ve accomplished your goal, and never second-guess yourself. Unflinching commitment is the only way to not get run over. The only difference is if you fall when climbing you usually don’t end up pancaked under an unforgiving five-ton bus. Ignore the trucks, cars, and motorcycles that head straight towards you as you confidently stay your course; they’ll swerve away at the last moment…have faith.

Jodhpurians cannot be bothered with using side or rear view mirrors. In fact, such luxuries are conspicuously missing on many vehicles. To be a good driver here in India one is required to never take their eyes off the road directly in front of them…ever. Vehicles ahead of you always have the right of way, no matter how many intoxicated, swerving turns and variations they wish to make without any indication. When overtaking you first have to blast your horn obnoxiously for at least five seconds. Then, when the forward vehicle (without looking behind) senses your intentions and eases left, you gun it…always glaring at the annoyingly complacent other driver as you smother him with toxic petrol fumes.

It is exceedingly fascinating, if not surprising, that such a system of unwritten traffic law works as well as it does; I think that it warrants the attention of sociologists, or whoever it is who studies this sort of behavioral phenomenon.

--------------------------

One of the many reasons why I have so quickly fallen for this city is that its residents seem to love food nearly as much as I do. Food is everywhere: in limitless restaurants and guesthouses, on street corners, in markets, on portable push-carts, and in the military style, stainless steel lunchboxes that everyone carries with them. The cuisine of Rajasthan is unlike most of the normative Indian food found in America. Molded adaptively by the limitations of a desert environment, everything is cooked with minimal use of water. The food is oily, buttery, greasy, creamy, and deep fried to delicious perfection. In fact, I can feel myself getting fatter as I write these words.

Last week I ventured to a restaurant called “Gypsy,” my guidebook’s most highly recommended eatery. They served only one thing: an all you can eat, seven-course veg. thali platter. I had four waiters assigned to my table. Now, when I say that they were assigned to my table, I mean it. These four bow-tied young men stood at attention, not two feet from my table, awaiting indication that I was ready to gluttonize myself with more aloo gobi, dhal bati, or steaming hot roti. After two hours of performance eating, my stomach satisfied that it had received its money’s worth, I paid the bill and left. Including the hundred percent tip, the extravagant meal had cost me nearly three dollars.

Have I forgot to mention that I love this town?

No comments:

Post a Comment