Work can sometimes get very frustrating. The villages are incredible. I have enjoyed every minute of my village visits and I am sure that those experiences have changed my life in ways that I cannot yet fully comprehend let alone articulate. When I am not visiting the villages my days are spent writing at the Veerni office. I have written the organization’s annual report, proposals for the continuation of funding from our donors, a presentation that was given at an international health conference, reports in specific Veerni programs, and this week I finally finished writing a report on a study that I developed and administered at Veerni’s boarding school for girls. I enjoy writing about things that stimulate me. And what Veerni is doing here in Jodhpur is important. We are affecting a centuries-old, destructively patriarchal social structure, ensuring that the young women of today and future generations enjoy the most fundamental human right: the opportunity to choose one’s path in life. I love to write, and I take pride in producing quality work for Veerni. Therefore, I get frustrated with my job when the resources necessary to produce professional writing are unavailable.

Two weeks ago my patience with the inefficiencies and disorganization at my office was pushed to its limit. I was tired, stressed out, and found myself to be short tempered with my well-intentioned coworkers. I needed a break, and so I felt justified in asking my boss for permission to take a three-day weekend.

I packed my messenger bag that night. An extra shirt, a tie-dyed bandana, and my camera were all that I would need for a weekend in Pushkar. I had just finished my book so I traded it for another from the guesthouse’s library, a collection of fifty worn paperbacks representing at least ten languages. I slept through my alarm on Friday morning and rushed out the front gate at 8:00am, eager to begin the six-hour drive. As I motored through waking Jodhpur chai wallahs were just beginning to stir their steaming teapots, preparing for the early morning rush of weary decaffeinated workers. Stopping at a fruit stall, I filled the remaining space in my bag with bananas, plums, and harpoose mangoes. The shopkeeper eyed my 150cc bike with skepticism when I told him that I was on my way to Pushkar.

The first twenty kilometers were familiar, following the same road that I have taken many times to the village of Meghwalon Ki Dhani. After leaving the familiar singlewide I had nothing left to guide me but the kindness of strangers and the scrap of paper upon which I had written, in Hindi script, the names of the villages along my chosen route. For fifteen kilometers I rode on a well-paved two-lane road. I had clear sight for miles ahead of and behind me, so, seeing that the road was clear, I opened up the throttle. Traveling fast enough that people in the fields on either side didn’t seem to notice me, I realized that I was invisible. I know that it sounds trivial but, honestly, not being noticed here is a noteworthy part of my day. Some of the looks I get on the street are startling; sometimes people stop whatever it is they were doing to gape, slack-jawed, until I smile and wag my head, which usually snaps them out of their fixated trance. But, now, charging across the desert nobody even glanced at me. It was my turn to stare at them!

It was easy to space out, ogling at the dusty sanitized landscape that blurred past. I had to be careful though. There are many roadside vendors out there, seemingly in the middle of nowhere, who sell cold drinks, paan, and beedis. Their enticement strategy, although dangerous for motorcycle-bound daydreaming foreigners, is actually quite brilliant. To get motorists to slow down enough to see what the stall sells, some vendors create a speadbreak, either in the form rocks, branches, or crudely poured humps of crumbling concrete. I learned my lesson after almost being thrown over the handlebars; as with other features of life in India, I have found it wise to assume nothing and expect anything.

At the first unexpected fork in the road, I pulled into a dhaba hut to get a drink and ask for directions. In Rajasthan, people store drinking water in clay pots so that it remains cool. A communal cup sits on top of the plate that covers the cistern. This aluminum cup has an outturned rim that enables the user to waterfall liquid directly down their throat in an alternately gulping and then gasping fashion. In this way, the whole pot is not contaminated by the touch of lips. Removing the plate and peering inside can be a mildly nauseating experience. Depending upon how long the water has been sitting, varying viscosities of grease and slime glaze the surface. I have only been sick once and, even then, “Delhi Belly,” wasn’t so bad. It was no worse than mild food poisoning and I was fine after thirty-two hours. I have been drinking the tap water and eating the street food and, despite the morbid warnings in my guidebook, I feel no worse for it.

So, with slimy water dripping down my chin and onto my shirt – the waterfall method has not yet been perfected – I asked one of the men in the hut to kindly tell me which road led to Barunda, the next town on my scrap paper route. The first man to speak up, in Marwari, told me that the right-hand fork led to Barunda and that, coincidentally, he was heading there as well. Now, I don’t speak Marwari, the tribal dialect that roughly translates to “the language of the land of death,” but I have found it remarkable how effectively communication can be achieved through inflection, gestures, and facial expressions. I told the tall Rajput man, in English, that I would be happy to take him to Barunda and, leaving the chuckling group of men in the hut, we motored away, taking the right-hand fork out of Pipar. In Barunda, the appreciative man begged me to take chai with him at his house but I politely declined. I had gotten a late start and, already, the desert furnace was heating up.

Continuing on across the barren landscape, I slowed down when passing shepherds, fearful that one of their goats would foolishly dart in font of my bike. Occasionally a solitary bull would appear, rising out of the oil-slick mirage miles ahead. When this happened, I found myself whistling the theme to, “The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly,” as if I was facing down a gunslinger on a deserted western main street. Once close enough to see that the bayonet-crowned bovine was clearly top gun in those parts, I would swerve to the other side of the road to give the lazy beast ample space for whatever it had in mind.

I passed through Merta, Piras, and countless other remote towns. Sometimes, spotting an inviting tree, I would turn off the road and bump across rocky unplowed fields to enjoy a mango in shaded solitude.

With only half an hour's drive remaining it began to rain. Seeing no shepherds, I sped up and finally arrived, drenched, at the first hotel whose name I recognized from the guidebook. The hotel was too expensive but I cringed at the thought of returning to the steaming, flooded streets.

During monsoon the benign open sewers overflow and spill into low-lying areas, forming rivers and pools of putrid slush. You can only drive so far on a motorcycle with knees tucked timidly to chest before you have to lower your feet for a downshift or hard brake. Being covered in sewage isn’t so bad; it’s the prospect of having to do it again that gets you reaching for your wallet.

Besides, the hotel had a swimming pool, a luxury that I was willing to be overcharged for. For the remainder of the rainy day, I swam, napped, and finished the well-read book that I had stolen from the guesthouse.

---------------------------------

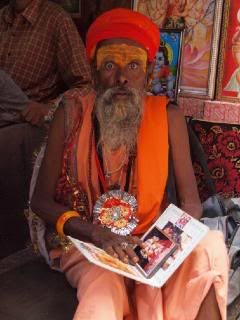

I didn’t sleep through my alarm on Saturday morning; I wanted to get an early start on my hike. Pushkar, a town of 14,000, one of India’s holiest pilgrimage sites, is an oasis in the desert. In the northern foothills of the Aravali Range, the town itself has been built around a lake, a basin scooped from the surrounding jungle-green peaks. When the world was created Brahma dropped a lotus petal into its ocean. Where it floated to the surface, according to legend, became Pushkar. The lake at the center of town is ringed by fifty-two bathing ghats, the most auspicious of which leads down from the Brahma Temple, one of only a few such temples in the world. While it is undoubtedly the most important temple in Pushkar, it is but one of over 500 that sprout from the city and surrounding forests. The town, owing to its reverence of the cow god Lord Brahma, is strictly veg-only and alcohol-free. Cannabis, however, is openly consumed in the forms of hashish or bhang-lassi, a potent yogurt drink that is sold at restaurants and roadside stalls. As such, Pushkar has a heady atmosphere that caters to the hippy travelers who throng there.

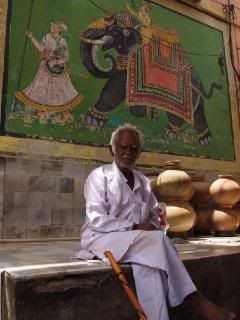

I drove my motorcycle to one of the ghats, weaving cautiously through the mass of Indian pilgrims and stoned European tourists. After performing puja with the help of a Brahmin priest I rode to the outskirts of town where I would begin the 1000-foot climb leading to the sky-scraping Savitri Temple. It was at the base of the towering hill that I met Shyam Lal and his wife Endra.

As I parked my bike near his chai dhaba he beckoned me over and, after spirited conversation, he offered to watch my helmet for me as I hiked. I thanked him with a palms-pressed “namaste” and promised to take chai with he and his wife when I returned. The trail to the temple followed a well-worn stone staircase that crept and twisted over drainages choked with goatherds struggling to make it to the top. I hadn’t been walking for more than fifteen minutes when I turned and saw Shyam’s son, Anil, sprinting, scrambling to catch up with me.

“Bhanjeemoon-ji,” he panted as he finally reached me. “I walks with you?” he asked exuberantly.

“No, it’s alright,” I told him. “I don’t need a guide.”

“Ji nahi, only friend, only talk, no money,” he responded.

“Ok,” I relented, fully expecting to pay him for his service when we returned to the base of the hill.

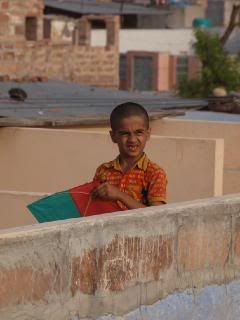

Although Anil looked to be about twelve years old, he told me that he was seventeen while his father later informed me that he was, in fact, fourteen. I was very impressed with his English, especially after I learned that he had never before attended school, and we conversed easily for the remainder of the climb to the top.

The temple wasn’t nearly as spectacular as the views that it afforded. The farmed valley spread to the horizon like an organic patchwork quilt. Seeing it from above, I realized that the town was even smaller than I had initially thought. I could see Shyam Lal’s chai stand, just a speck among countless specks. I imagined him squatting over his steaming pot of creamy tea, every now and then peering up the winding path.

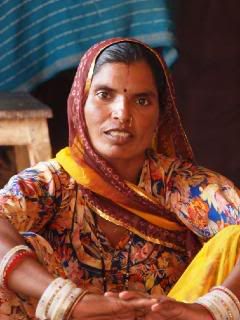

When Anil and I did return, the chai was not yet ready. I played with Shyam’s four other truant children while he tended to the frothing pot. After tea and talk the family led me up a neighboring hill to their humble home. Crammed into a narrow space between two just like it, the single-room plaster hut was two paces deep and four paces wide. Windowless and without a bathroom, the Lal’s home was decorated with practical wall hangings: a yearly calendar of important Hindu dates, tin bowls, plates, and ladles. One of the walls had become a shrine dedicated to various Hindu deities. Above the prints, postcards, and drawings of multi headed, multi limbed, and fire-dancing gods was a faded framed photograph of a young, chubby-cheeked boy.

The father’s voice wavered as he told me how much he had loved his first-born son. There were no beds, or cots, or even cushions; just a few frayed cotton blankets, all of which were spread out for me, their guest, to sit on. I hung out with the Lal’s for some time before deciding to leave to go explore the main bazaar.

“Come back for suppers at six o’clock,” Shyam told me.

“Absolutely, I would love to,” I beamed, stealthily slipping to Anil, my guide, a fifty-rupee note as we walked back to my motorcycle.

At six o’clock I returned to the hut on the hill. The children were thrilled with the box of pistachio sweets that I produced from my satchel. Endra stirred a pot of Dhal Makhani as her daughter, Jiji, kneaded paratha dough on the cold cement floor. We ate, talked, and joked for hours until the retreat of the fire’s last glowing ember left us in darkness.

Over the course of the evening I had noted Shyam’s curious interest in my feelings about chicken. I told him that I thought chicken to be both healthful and delicious. He quickly made it known that he too shared a proclivity for poultry and so we decided that the following morning Anil would take me to an off-the-map Shivaite temple while Shyam would travel to Ajmer, a nearby city, to purchase a chicken for our lunch. I gave him three hundred rupees (six US dollars), enough for the price of the bird and his two-way bus ticket.

-------------------------------

The doorman at my hotel clicked his heals together, straightened his pointed spear, and saluted me as I avoided his gaze. Distant, suppressible pangs of guilt or disgust crept over me as I settled into my plush, air-conditioned room, my thoughts drifting to the family of seven snoring on the cramped stone floor of their hut on the other side of Pushkar.

-------------------------------------

The younger children, Raual and Gijndr, were sitting on the side of the road, waiting for me, when I rounded the bend the next morning. Jabbering gleefully in Hindi, they climbed onto the back of my motorcycle for the short ride to their father’s chai stall. Shyam Lal was still in Ajmer, buying our chicken, so Endra made chai for Anil, his friend, and I. Afterwards, the two teenagers squeezed onto the bike and the three of us took off heading south out of Pushkar. Judging by Anil’s uncontainable excitement, I knew that he was leading me somewhere special.

The rolling road was deserted. We drove past rain-logged patty fields and through narrow walled canyons. At one point a dust covered woman, standing in the middle of the street, signaled for me to stop. As I shifted into neutral a tremendous blast exploded from the crags above. A geyser of rocks and smaller pebbles showered the path ahead. I snaked the bike through the rubble as the woman, a quarry worker, waved me on.

“Turn here,” Anil shouted over my shoulder.

“Where, here?” I shouted back. Surely he couldn’t have meant where I thought he did.

“Here!”

We turned off of the road and onto a goat trail that I could see twisted up into the mountains ahead. Bouncing over shifting rocks and across trickling streams I prayed that the quality of the path would not degrade any further. I struggled to keep the motorcycle upright as it chugged over a shale-covered rise, the rear tire projecting slate missiles with every over-rev of the engine. We fishtailed, slipping and sliding down sandy declines, six flailing legs outstretched like supports on an outrigger canoe. It was a feat of strength and will that kept us from capsizing.

On the final decline, however, I lost it. I was going a little too fast and the boulder-strewn step-downs were too big. By the time I knew that we were going down, Anil and his friend had already thrown themselves clear and were trapped, limb twisted, in a stand of nearby thorn-bush. I credit my survival to the crash experience that I have developed through many seasons of borderline reckless skiing. Or maybe, and I prefer this theory, after years of climbing I now have a karmically favorable relationship with rocks. In either case, I too had cleared the bike before the front wheel locked and it tumbled down the hill, finally stalling out in a muddy ditch. Removing my helmet and checking for missing or impaled body parts I looked up as Anil and the other boy, unphased, scampered down the hill and past the defeated motorcycle to the banyan shrouded temple.

As I followed them on foot I noticed that there were peacocks everywhere. There were dozens in the trees and even more strutting about the grassy temple surroundings. Monkeys bounded over rocks to drink from the temple’s pools. Pairs of them sat in the sun taking turns grooming each other. They swung from vines and branches and always snarled when I got too close. The temple itself sat in a depressed mountaintop valley among hundreds of colossal boulders and incredible rock formations. As I caught up to Anil he pointed at a truck sized boulder and asked, “You see Ganesh?” On the stone to which he pointed was a naturally formed image of the elephant god whose “trunk” devotees had painted white.

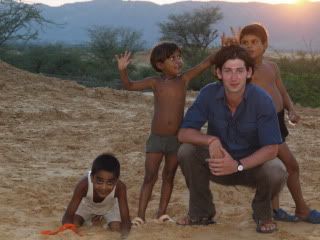

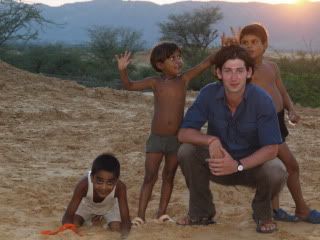

I watched the boys perform puja at the temple’s stained lingam – a carved phallic representation of Shiva – and afterwards explored the area with them and a few other kids who appeared and decided to tag along.

To my surprise the motorcycle had not been damaged in the crash and it roared to life on the first kick-start. After a quick stop to collect wild peppers for his father’s curry, Anil, his friend, and I veered back onto the main road. Zooming past the quarry and the flooded fields, the boys were thrilled and held their arms out as if they were flying.

By the time the three of us sauntered into the Lal’s front yard, Shyam had already killed and cleaned the bird and was carefully studying it as it simmered in a pot of boiling water. Anil told me to follow him, that we needed to get something else for the curry, something he didn’t know the English word for. I assumed that we were heading to the market but instead he led me to a stand of clustered trees further up the hill.

“There…very tasty,” he exclaimed as he pointed and knelt to pick the two-dozen mushrooms that poked through the underbrush.

When we returned to the hut, Shyam presented me with a steaming gray slab of spongy meat. I figured that it was an honor to be given the liver, the most protein rich part of the bird, and so I gobbled it down with a smile. A few beedis later and the stew was finally ready to eat. It was delicious, spiced with garam masala, fresh wild peppers and mushrooms, yellow squash, and gourd.

After mopping up my second helping with endless piping hot chipati I realized that it was getting late and that I should begin the trek back to Jodhpur. I talked with the family a little while longer, exchanged contact information, hugged, shook hands, patted heads, and turned around one last time to wave goodbye as I motored away.

The six hour drive was uneventful by Indian standards; I gave a few more rides to random villagers, only got lost once, and arrived safely back in the Blue City at around ten o’clock.

The weekend in Pushkar was exactly what I had needed. I felt refreshed by the unexpected hospitality that the Lal’s had lavished upon me. My workplace stress had effectively dissolved and that giddy love for this country returned and lingered for days thereafter. I don’t think that my first encounter with that incredible family will be my last either.

In October the desert oasis hosts the Pushkar Camel Mela, an event that draws a quarter million dromedaries, and which is now considered to be the largest livestock fair in Asia. The weeklong mela is complete with races, camel beauty contests, folk art, music, dance, and spirited Rajput mustache competitions. Shyam begged me to come stay with his family for the festival and I fully intend to take him up on his generous offer.